"Detoxing Narratives" – Pictures

The aim of our workshop “Detoxing Narratives” was to explore how “other stories” can be told in “different ways”. We organised this come together to open a floor to counter-narratives to what we can hear on the news and read in newspapers. Unreflected depictions include stories of violent refugees and a need for protecting one people from another kind by (re-)building walls, fences and other non-human devices. We are under the impression that the world is full of stories; stories that are being used to explain, understand, trade, and pass on ideas but also to justify actions and distinguish between “us” and “them”. In referring to stories tightly intertwined with social and cultural backgrounds, we strove to reveal alleged understandings of stories (and images) of different origin to re-tell stories (of the past) in order to gain new insights and to emphasise common grounds.

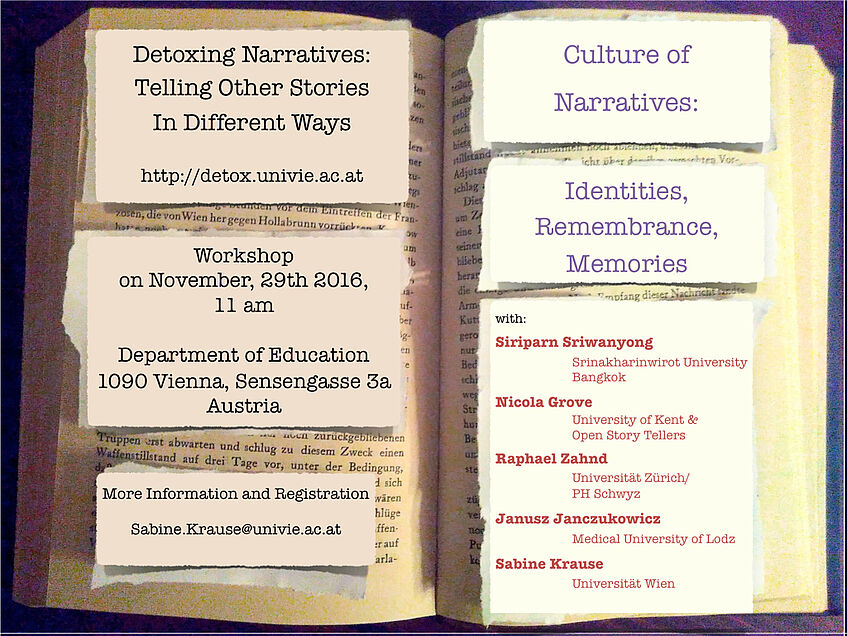

Setting up a storytelling workshop what we foremostly needed were reportable and tellable stories that are considered worth telling. Secondly, we searched for individuals who were able to tell these stories, master the art of forming - not necessarily merely verbal - narratives and mark them as relevant. We were successful in identifying four very interesting personalities who agreed to share their stories and tell their “other stories in different ways”.

Our first storyteller was Siriparn Sriwanyong (Srinakharinwirot University Bangkok, Thailand) from Thailand bringing along the the popular tale of Mae Nak, in which ghostly appearances give lessons about bonds in life, letting go and impermanence of life. In a permanent inter-play between reality and illusion, the movie used to visualize the story unfolds to not only tell the tale of Mae Nak but presents essential insights in Buddhism, too. Siriparn emphasised the importance of his example as it is a key story for children to learn to read cultural codes and symbols and to gain knowledge about and understandings of Buddhism. This tale is told in various variations and it is implicitly and explicitly referred to in many different ways in Thailand. Everyone is said to know the story of ‘Mother Ghost’. Thus, it can be stated that it serves an educational purpose and is central for an interpretive understanding of Thai culture.

Raphael Zahnd (University Zurich / PH Schwyz, Switzerland), our next storyteller, comes from Switzerland and intended to make a case: A nation arisen from a multitude of different tribes, fused to jointly fight the enemy. Does this story make the nation able to handle differences and diversity well? Paperclips from recent years told us otherwise. Raphael presented an amalgamation of three different stories of the foundation of Switzerland with an enlightening conclusion: the myth of strong bonds to fight jointly for common rights brings with it toxic narratives, too. The custom of re-telling the foundation myth, which is meant to be an act to celebrate the differences in unity, is clearly a narrative of distances to others: The foundation mythos of Switzerland bears in it the idea of people who do not want to belong to others. The structure of those myths helps to create distinguished habiti that in turn draw strict lines between groups and uphold ascriptions to self and others.

The reflective discussion of these two presentations brought to light three things. First, it seems that we are in need of heroes: a person or a group, suffering from anguish or repression is freed from it to grow stronger for a better future. But heroic stories tell just one part of what is going on; the focus on a single person or group clouds all other things, which might be of interest. Second, we need these stories to reaffirm our social and cultural belonging; in this understanding storytelling forms part of educational processes. Third, even if storytelling is essential for feelings of belonging, we have to reconsider those narrations, tales and stories and to introduce counter-narratives or stories of the forgotten past to overcome misconceptions and misinterpretations.

Nicola Grove (University of Kent / Open Story Tellers, UK) told “Stories from the Margins”: as a storyteller who tells stories with people with intellectual disabilities, she is especially aware of the fact that “those who tell stories and make people listen to run the world”. If one is deprived of chances to communicate and make oneself heard, it does not matter how many stories and tales one has to tell or as one wants to tell… no one will listen. So part of her work, and an assignment to all of us, is to be creative and find ways to tell stories with, for, and about all the people the stories belong to, to make sure that all have the chance to “run the world”. But once a narrative gains traction we have to take a closer look on what is told (What is the story about? Who are the [main] characters? What is happening to them?), how is it told (Which words are used to narrate and describe? Where is the emphasis? What is not told?), and how do we listen to those narrations. And after all, there might be a truth hidden in (traditional) stories. Nevertheless, Nicola stresses that we have to understand that truth is not important. Narrations are about identifying with others and connecting them with ones own experiences in life.

With Janusz Janczukowicz (Medical University of Lodz, Poland) we entered the realm of oral testimonies about living in a foreign country. The history of Poland, the country we are talking about, makes a special case: having been play-ball to several political regimes over time, Polish people formed a closed community that relies on a “don’t ask-don’t tell”-tradition. This tradition can be interpreted as a vacuum in shared oral heritage; talking about hi/stories in Poland is therefore asking for verbalised knowledge of the own culture to understand what we know and what we do not know. Janusz concluded that only an awareness of the own collective background and the reassurance of a common good lays ground for different notions of “us” and “others” that can help to build a public spirit of acceptance.

The workshop was wound up with a reflection of the stories and storytelling. It was shown during the sessions that cultural heritage and traditions are normative and formative elements of our social and cultural life and that storytelling is one element in it. Stories, tales, custom, and traditions are formed through time and space: in reiterations we strengthen those existing forms and underlying concepts that are deeply woven into socio-cultural ways of being. But reiterations are always situated performances in current settings and thus can help to alter or overcome inherited and adopted forms and norms. This workshop on storytelling was one approach to point out regimes that shape our ways of seeing, telling, and listening. It was a first step to re-read stories and ask other questions; it implied to invite various contributions, to share unknown stories, to establish listening as a skill, and to remember that telling emerges during the process. For “Telling Other Stories in Different Ways”.